Ilíiaitchik Correspondents Learn the Art of the Interview

Photo Credit: JoRee LaFrance

“The key to being a good interviewer is being a good listener,” advised Valerie Vande Panne, Mentor/Editor for IRes’and Planet Forward’s Ilíiaitchik: Indigenous Correspondents Program. This was one of many lessons learned by Indigenous Correspondents during the Ilíiaitchik program’s second workshop titled “The Art of the Interview,” which was co-led by Vande Panne and former CNN correspondent, Planet Forward’s founder, and Emmy-award-winning journalist Frank Sesno. During the two-hour session, Correspondents learned the following skills for conducting rigorous, respectful, and compelling interviews:

- How to find the “right” person/ people to speak with for telling a story.

- How to prepare for a successful interview and how to create a comfortable environment for interviewees.

- How to take notes during interviews that best capture the essence of a conversation.

- How to prepare questions suited for different interview types, such as celebratory interviews, informational interviews, investigative interviews, etc.

- How to navigate interviews with different Indigenous community members, including tribal Elders, elected officials, knowledge-holders, etc.)

For the first half of the workshop, Valerie shared with the Indigenous Correspondents the importance of being attuned to local needs, cultural values, and ethics when interviewing Indigenous community members.

“Whether you are speaking with a tribal Elder, a Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, or a knowledge-holder, you need to listen and learn before you start asking questions” advised Valerie. As she explained, being sensitive to cultural nuances and knowing when not to ask questions is just as important as knowing when and what to ask, especially when working within Indigenous communities.

Valerie Vande Panne

©2021 Two Eagles Marcus, LLC / GlitterBooth.com

Striking a balance between asking and listening, as well as knowing when to record and when not to record or share information, is especially critical in Indigenous spaces when access to knowledge is oftentimes dependent upon cultural values unique to each community. For example, knowledge about the precise location of sacred or ceremonial sites might only be considered suitable for particular individuals to know, based upon their age, gender identity, and/or status within the community. With well over 574 tribes across the United States - many with different languages, unique cultural values, customs, and governance structures - journalists need to approach each meeting with humility to learn who has authority to speak on a given topic and what can be shared and discussed.

As Valerie noted, knowing when to ask and when to slow down all comes down to building a space for comfortable dialogue to take place. As reporters and storytellers, we can show respect to the knowledge and experiences shared during conversations, as well as our interviewees’ time and energy, by asking the person or people with whom we are speaking what they are comfortable sharing, moving at their pace, and confirming precisely what information can be shared beyond the conversation (ideally at several points throughout the editing process before publication).

Unfortunately, journalism far too often runs on an extractive model wherein journalists are positioned as interrogators of sorts, seeking to extract information from interviewees with little or no regard for how sharing peoples’ stories might impact, or benefit the person themselves or those around them. As Valerie acknowledged, a harmful power imbalance often exists between the interviewer, with their perceived ability to steer conversations through targeted questions, and the interviewee, whose stories, experiences, and knowledge are being taken and shared for profit. These power imbalances and extractive practices are rooted in Western storytelling practices, which historically are unidirectional transactions as opposed to two-way dialogues aimed at building mutual understanding and support.

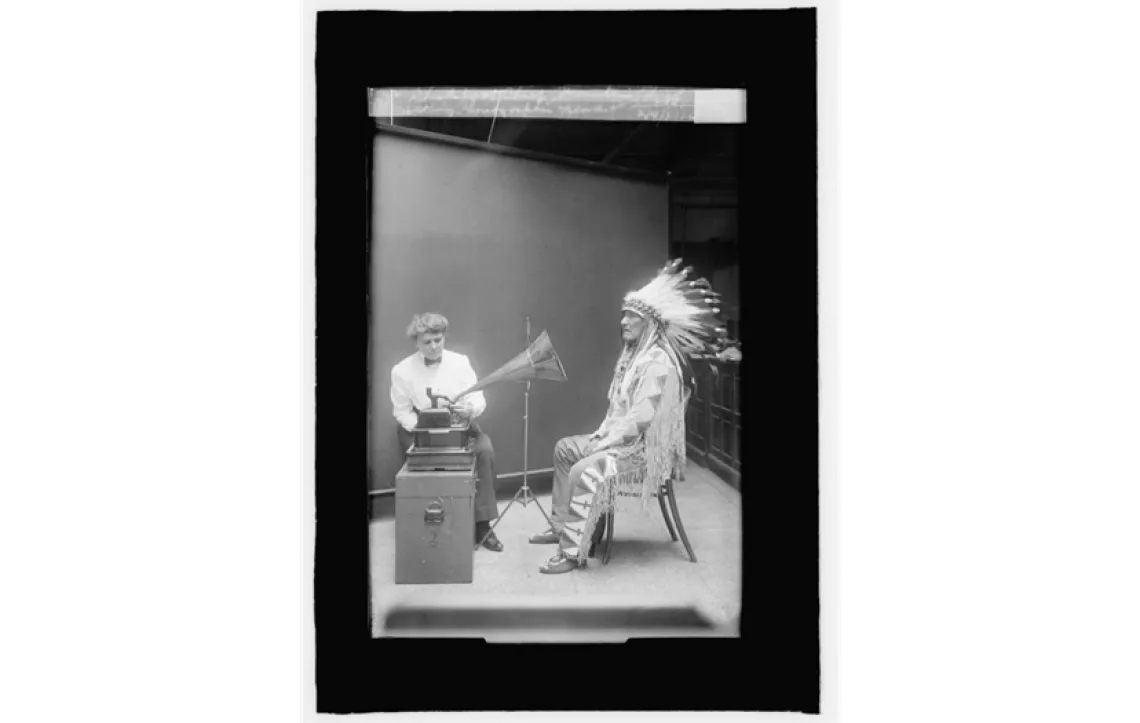

For far too long, researchers and journalists have conducted interviews without the full consent of Indigenous communities, or with little to no regard for how information collected might impact Native people. In this 1916 photograph, U.S. ethnologist Frances Densmore records Blackfoot leader Ninna-stako, also known as Mountain Chief, interpreting a cylinder recording. In this instance, Mountain Chief approached Densmore with an interest in preserving Plains Sign Language, however many other photographers, ethnographers, and writers captured photographs, recorded audio, and transcribed stories since colonization without fully-informed consent. While these recording practices are now more uncommon, power imbalances and mistrust still persist between many media outlets and Indigenous people today.

Image courtesy Library of Congress; digital image npcc 20061: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/npcc.20061

In addition to western media’s focus on profitability, the extractive nature of most interviews is attributable to a mix of factors, including the demand for fast-paced, sensationalized stories, thirst for exposés that catch interviewees off guard, devaluation of non-academic and non-scientific forms of knowledge, and the decline of locally-based print media and journalists who historically served as a continued presence within their communities. These extractive and colonial journalism tactics not only produce less compelling narratives - but they can also harm Indigenous communities. For example, when conducting interviews with a Tribal Historic Preservation Officer or other tribal officials, speeding through an interview and then rushing the content through to publication limits the ability of community members to respond in a culturally-appropriate review process that may require discussions to be had and approval to be gained by tribal leaders and elders. Providing ample opportunities for interviewees to ask clarifying questions, such as the intent behind asking a question, publishing a story, and who the interview information will be made available to - helps protect Indigenous data sovereignty, which the University of Arizona’s Native Nations Institute defines as “the right of a nation to govern the collection, ownership, and application of its own data. It derives from tribes’ inherent right to govern their peoples, lands, and resources.”

Valerie noted that long before conducting interviews, “Reporters need to give of themselves, and spend time in a community… such as going to basketball games and community events, and just listening, before ever asking a single question for a story.” Building connections and relationships with communities takes time well in advance of reporting, but is critical for building trust, greater understanding, and humility. By volunteering at a community event or being fully present to celebrate local accomplishments and meet with community members, storytellers also give of their time, energy, and/or expertise in return for the time and expertise community members give during interviews. Doing so can help make reporting less extractive and more reciprocal.

Frank Sesno provided complementary advice during the second half of the workshop, noting “You have to approach interviews with an intense interest in what the other person has to share - not just in the questions you hope to have answered. Even if you don’t share perspectives or you're not particularly fascinated by your interviewee’s area of work or study, find something about their story that you are compelled to learn more about and hold onto that interest throughout the conversation.” By focusing both on the interviewee’s story and the story you envision telling, stories are better able to evolve organically.

Frank Sesno is an Emmy Award-winning journalist and the creator of Planet Forward, a multi-media storytelling platform that celebrates sustainability and science - and supports the Indigenous Correspondents Program.

Image courtesy Frank Sesno.

Frank explained how approaching an interview with a conscious goal or outcome helps frame the questions and the conversation. Some interviews, he noted, are meant to gather factual information. Others seek a personal perspective or analysis. Still others may revolve around the accomplishments or impact of a featured personality and require the kind of detail and storytelling that makes for a great profile story. Frank said that if interviewers have a sense of what they’re looking for - while still listening for surprises and pursuing the unexpected - they will prompt rich, focused conversations that can be respectful and genuine, inviting people to open up. That approach, Frank pointed out, also supports active listening, genuine curiosity, and relevant follow-up questions that an interviewer should bring to every assignment.

One of the core takeaways from the second Ilíiaitchik: Indigenous Correspondents Program workshop was the need for storytellers - especially those planning to work within and for Native communities - to approach interviews with humility, transparency, and clear intent. Rather than approaching interviews as unilateral opportunities for asking questions and note-taking, we need to see interviews for what they should be - balanced, multidirectional conversations where both parties have sufficient opportunities for listening and learning. Since many Indigenous Correspondents aspire to tell stories from their own communities, conducting balanced interviews takes on even greater importance. As Indigenous storytellers, we hope to build and maintain relationships grounded in trust, respect, and reciprocity when doing communication work. To do this, we need to be aware and respectful of each community’s cultural and governance structures surrounding sharing information, as well as when it isn’t appropriate to ask questions. Knowing when to listen is just as important as knowing when to ask for more explanation or to delve deeper into an experience or perspective.

As Indigenous Correspondents, we aspire to tell stories that benefit and uplift our interviewees and their communities, whether through exposing environmentally unjust conditions and holding offenders accountable, or celebrating local ingenuity, artistry, and accomplishments. To be effective storytellers, we should always ask our interviewees what they hope will come out of sharing their information - being sensitive to community needs helps restore balance between the interviewee and interviewer. To maintain this balance, we also need to make clear the intent behind asking questions, where and when the information will be published, and who the audience will be. All of this is to say that interviewing is about so much more than just asking questions - it’s an art that requires adequate time, humility, active listening, and balance.