Insights into Environmental Storytelling with National Geographic Photographer Kiliii Yüyan

Above: Kiliii Yüyan shared how this portrait came together: “The Rangers suggested we shoot amid the flames, saying, ‘We want to show people that fire is not something to be afraid of, that fire is a friend.’”

On the northeast coast of Australia lies the world’s oldest continually surviving rainforest, home to many indigenous Aboriginal groups and thousands of animals and plants. Despite its UNESCO World Heritage status, species biodiversity in the Wet Tropics has declined in the region. While Western scientists have struggled to understand this trend, local Aboriginal communities have recognized an absence of traditional fire stewardship as a major factor.

National Geographic Explorer Kiliii Yüyan (Hèzhé/Nanai) highlighted this critical insight during the Indigenous Correspondents Program’s "Insights into Environmental Storytelling" workshop in November. Reflecting on his work documenting cultural burns in the Wet Tropics, Kiliii explained that, “Aboriginal peoples lit fires frequently and regularly to manage their landscapes, benefiting both plants and animals. Since colonization, the lack of these fires has led to habitat loss and species decline.” His work, featured in the July 2024 issue of National Geographic, celebrates Indigenous-led conservation efforts like those of the Irukandji and Djabugay knowledge holders who are returning cultural fire practices to the rainforest.

Kiliii emphasized the importance of community-centered and place-driven storytelling, which he employs to illuminate the unique strengths of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). He contrasted TEK’s generational, communally-held, and land-based understanding with the narrower data focus of Western science, noting, “Traditional knowledge is different in every region. As storytellers, it’s our job to understand and share what makes it special.”

Above: Kiliii Yuyan described how he sought to visualize Iñupiat spiritual practices during whale hunting, where gratitude is central. Reflecting on this photo, he shared: “Flora walked up and put her arms out… That is their way of saying thank you. It’s a symbol of gratitude to the whale, so vital to their community.”

Drawing from his ongoing project "People of the Whale," Kiliii shared how Inupiat whaling communities in Alaska have successfully increased bowhead whale populations from 8,000 to 17,000 over 30 years while maintaining traditional hunting practices. This achievement, rooted in TEK, demonstrates how culturally grounded stewardship can complement conservation efforts. “In two-eyed seeing, we do both science and traditional knowledge, but we need to show the world why traditional knowledge matters," he said.

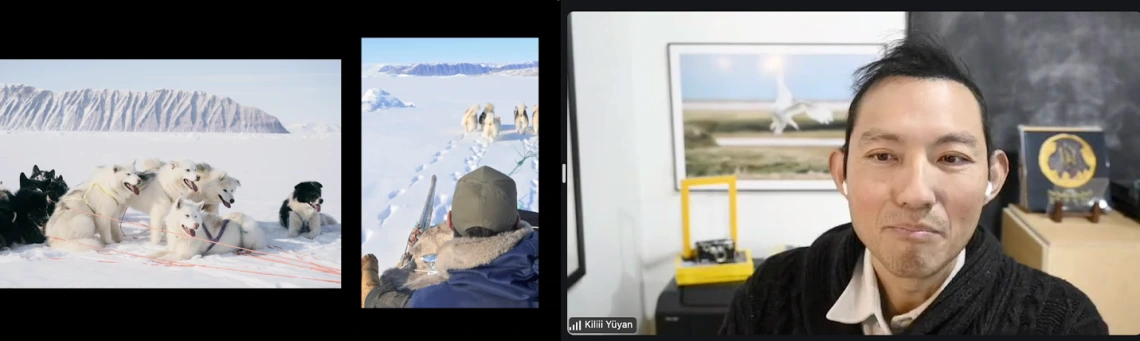

Kiliii also described the importance of being adaptive and flexible when going on assignment. He described a storytelling trip in Greenland where climate change disrupted the narwhal hunt he initially planned to document. “I realized I had spent six weeks on the back of dog sleds. That became a greater part of the story,” he recounted. By shifting focus to the sled dogs that provided not only companionship but also critical transportation, he highlighted their cultural and ecological significance amid the challenges posed by climate change in the Arctic. "The dog sled is central to life here—essential for hunting, travel, and connecting communities. It’s a lifeline.”

Above: After spending time with the Inughuit, Kiliii Yuyan focused on sled dogs, central to life in the Arctic. “This is the land of the dog sled... Qaanaaq has more dogs than people, and the Inughuit have relied on them for thousands of years. Dog sleds are reliable—they can’t run out of gas.”

One of Kiliii’s key takeaways for workshop participants was the need for depth in storytelling. "The difference between journalism and distraction is insight," he explained. In a world saturated with information, meaningful stories reveal the complex relationships between people, places, and issues. For example, Kiliii’s images of bowhead whale hunting emphasize community ties, family relationships, tradition, and gratitude – relatable aspects that can help audiences connect with practices they might not otherwise be knowledgeable of. Kiliii urged storytellers to seek insights that resonate with their audiences and inspire action. “Without depth, a story is just noise,” he said.

Above: Kiliii Yuyan shared a photograph of an Inupiat whale hunt, highlighting the community effort required: “Whaling is community. It takes a village to pull up a whale...” He also noted the impact of climate change, which is visible in this photograph: “You can see the broken chunks of ice... The warming Arctic Ocean has changed so much that in some years, there’s no ice thick enough at all.”

Killii also challenged the student storytellers to re-examine prevailing notions that: a) a compelling story is one “that highlights something we’ve never seen before”, and b) “everything has already been seen.” He noted that much of what we see in journalism reflects dominant, Western, mainstream worldviews. Rather than finding “something we’ve never seen before,” he encouraged the students to highlight perspectives and worldviews that have been too often overlooked, excluded, and/or marginalized. By centering diverse viewpoints, even familiar topics can reveal fresh insights and resonate with audiences in new, powerful ways. “A lot of the great insight, and thus storytelling, comes from perspective, which is why you guys are in such a great place” he noted.

Kiliii’s parting advice was to share stories that empower and support Indigenous sovereignty efforts. “Now, maybe with some concerted effort, I’m hoping that industrial values will change in 100 or more years. I'm optimistic, but I’m also realistic… What should we do in the meantime? I think the answer is simple. It's to trust and empower the communities around the world that already have sustainable, community-oriented values. And how do you support them? Fund them and support the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples over their land. That is what this storytelling work is all about.”

Above: Members of the 2024-2025 Ilíiaitchik: Indigenous Correspondents Program (ICP) ask Kiliii questions at the close of November’s “Insights of Storytelling” Workshop.